| Home | Chinatowns of the world | Festivals | Culture | Food Culture | History | Countries |

| Chinese Religion | Tours | Sitemap | Documentaries | About | Contact |

Mazu 妈祖

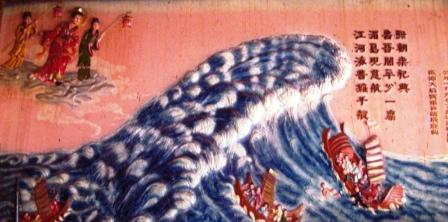

Temples dedicated to Mazu can be found in China and overseas Chinese communities around the world. These Mazu temples regard the Mazu Temple in Meizhou 湄洲 as the main temple. In Hong Kong, an MTR station, the local subway, is named Tinhau, 天后 as it is located near a well known Mazu temple. Macao 澳门 is said to be a Portuguese mis-translation of Mazu’s name. In 2009, the Mazu belief and custom was designated as "Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity" by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Other Chinese heritages in the list included the Dragon Boat Festival and Nanyin. Background of Mazu Her father was Lin Yuan, 林愿, and her mother’s family name was Wang, 王氏. When she was born, she did not cry aloud like other infants and was very silent even when she was a month old. Because of this, she was given the name Lin Mo, 林默. People often referred to her as Moniang, 默娘. Lin Mo had medical knowledge, was able to predict the weather, and could foretell the future. She was known to have saved seafarers in trouble and was highly respected and well liked by the community. Unfortunately, she passed away in 987 at the age of 28. After her death, a small shrine was constructed in her memory and there were various accounts of her appearing in person, sometimes carrying a lantern, or as balls of red light to guide ships in stormy weathers. The first written record of Mazu occurred in 1123 during the Song dynasty. A Chinese diplomat to Korea reported that Lin Mo appeared to guide their ships to safety during a storm. The Song Emperor bestowed Lin Mo the title of Ladyship and marked her rising influence among seafaring community in China. Subsequent Emperors honored her with additional titles and evaluated her status from Lady to Consort. In 1684, the Qing emperor honored her with the title of Heavenly Queen, 护国庇民妙灵昭应仁慈天后. Among the general population, the Heavenly Queen is popularly known as Mazu, a Chinese kinship term for highly respected female family members. Mazu’s birthday falls on the 23rd day of the third lunar month and is commemorated by Mazu temples around the world. Mazu as guardian of the sea During the Yuan dynasty, the Mongol emperors used the sea route to deliver grains from Southern China to their capital Dadu in today’s Beijing. The people involved in the transportation system worshipped Mazu and appealed to her for blessings and help. The Mongol emperor Kubal Khan, 忽必烈, honored Mazu with the title of Heavenly Consort, 护国明著天妃, in 1281. The Ming dynasty Chinese admiral Cheng Ho, 郑和 (Zheng He) prayed at Mazu temples before leaving on his famous sea voyages and Mazu was also enshrined onboard his ships known as treasure fleets 宝船 (Baochuan). During the late Qing dynasty, mass Chinese migration occurred and these migrants relied on Mazu for psychological support during their dangerous and stressful sea journey. As Mazu’s popularity grew, people appealed to her for assistance on other matters. These new requests are evident by additional powers attributed to Mazu. Mazu as the giver of sons Mazu in political culture During the early Qing dynasty, the Qing court paid tribute to Mazu for her assistance in recovering Taiwan from the Ming loyalists. This gesture was probably an attempt to shore up their political legitimacy and to gain popular support. Mazu in overseas Chinese communities During the late Qing dynasty, the Opium wars and internal chaos forced many Chinese to seek opportunities overseas. They embarked on a risky sea journey enduring difficult living conditions on board the ships. Under such high stress conditions, they could only appeal to Mazu for protection. Upon their arrival, they paid respects to Mazu for her blessings during the journey. When the community prospered, they built, restored, or expanded the Mazu temple in her honor as an appreciation for her blessing and protection. Mazu temples became the focus point for migrants to celebrate Chinese festivals or to participate in religious celebrations. See Yokohama Mazu Temple. Mazu temples can be found in almost every overseas Chinese community and hold memories of Chinese sojourners as they left China to seek a living and of their journey from becoming a migrant to becoming a citizen of their new homeland. Many of the Mazu temples are popular and well-known tourist sites. Some Mazu temples were transformed into Guan Yin temples as the local community’s belief or practices change. On the other hand, new Mazu temples continued to be built. Mazu is also manifested through spirit mediums. During prayer sessions or special days, the spirit of Mazu is manifested through a medium, usually a female, and leads the worshippers through rituals or offer consultations.

|

|

| Join us on | Youtube | |||

| Copyright © 2007-24 Chinatownology, All Rights Reserved. | ||||

Mazu, 妈祖,is one of the most popular Chinese deities worshipped and respected by commoners and the Imperial court since the Song dynasty, 宋朝. She was honored with imperial titles at least 36 times over a period of more than 700 years from the Song to the Qing dynasty. Mazu’s longest title was given in 1872 during the Qing dynasty and consists of 66 characters. See

Mazu, 妈祖,is one of the most popular Chinese deities worshipped and respected by commoners and the Imperial court since the Song dynasty, 宋朝. She was honored with imperial titles at least 36 times over a period of more than 700 years from the Song to the Qing dynasty. Mazu’s longest title was given in 1872 during the Qing dynasty and consists of 66 characters. See