Overseas Chinese in USA Overseas Chinese in USA

Anna May Wong, Charles Wong, Hiram Fong, James Wong Howe, An Wang, David Henry Hwang, Maxine Hong Kingston, Bruce Lee, B.D. Wong, Amy Tang, Wen Ho Lee, Richard Loo, Benson Fong, Patsay Mink, Michael Chang. Chinese Americans all. It is doubtful even today that the watery eye of the average American could identity each and every name, and the mark these men and women left on America. Anna May Wong, Charles Wong, Hiram Fong, James Wong Howe, An Wang, David Henry Hwang, Maxine Hong Kingston, Bruce Lee, B.D. Wong, Amy Tang, Wen Ho Lee, Richard Loo, Benson Fong, Patsay Mink, Michael Chang. Chinese Americans all. It is doubtful even today that the watery eye of the average American could identity each and every name, and the mark these men and women left on America.

It would take a conscious search to tell of the Chinese in the US. And yet, they have been there for almost two hundred years. A popular best seller floated the idea that the Chinese discovered America in 1491, a full year before Columbus. If true, they left no permanent trace nor did they colonize. War and social disruption in Qing China brought the first Chinese to the US in the 1800's, and war in Indochina broke the silence of the hidden history of the Chinese in America in the 1960's. The first Opium war and the Taiping rebellion brought the first Chinese mainly from southern China to California. There they mined for gold; there they sold their labour to build from the Pacific the continental railroad; there, too, they set up worked the land and the developing California's agriculture and fisheries; from there, they fanned out to all parts of the US which they called in Cantonese Kinshan or Golden Mountain.

You found Chinese in the defeated southern states after the Civil War working the fields of plantations; in Massachusetts, shoe manufacturers hired them as scab labour to break a nascent American labour movement, which triggered the joining of the two ends of anti-Chinese hostility in California and on the Atlantic seaboard, resulting in the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which among other things imposed onerous special taxes, denied citizenship, forbade marriage with whites. Before passing the Act, a heinous piece of legislation signaling out a particular ethnic group, heard in the houses of Congress were cries that the Chinese belonged to a 'despised race', untrustworthy, and unassimilable and inscrutable.

Thus, by 1882, we find the sealing of a concerted process to drive the industrious Chinese off the land, out of the mines, and out of any profession which would challenge Native American supremacy, and into ghettos which we know as Chinatowns. Thus, the Chinese faced with xenophobia, organized, falling back on the principle of self-reliance, a very American virtue much praised by Thoreau and Emerson, government through a benevolent association, business guilds, tongs and family clans, schools which provided order, work, and protection to the Chinese faced with Americans open hostility.

Saying this, although the Exclusion Act denied them citizenship, limited the number of Chinese women allowed in the US, offspring of theirs had the right to citizenship, and so to get around restrictive legislation, we find 'paper sons and daughters'; despite blatant racism, America looked the other way when it came to importing indentured Chinese labour or any Chinese workers in the US who worked for 'coolie wages'. And yet, Americans ventured into the exotic Chinatowns for opium, prostitutes, food adapted to their palate [chop suey, for example], and to feed fantasies of the mysterious east. The wages of sin and narcotics brought American missionaries to civilize the Chinese heathen.

Restrictive laws impeded the process of assimilation but through public schools and the use of Qing China's own indemnity monies, Chinese from China entered America's universities, and many didn't return home. The number of Chinese increased through births and illegal emigration, as slowly but surely did Americanization of children born on American soil; still, the persistence of American law and racialism kept Chinese in America on the margins of society. It is true, in cities and towns, one found Chinese hand laundries and a Chinese restaurant or two, or among the monied folk, a Chinese houseboy or cook, but to all appearances, the Chinese remained invisible.

Hollywood in its infancy and maturity, is a good indicator of America's perception of Chinese in America: he is an arch villain in the guise of the formable, evil Dr. Fun Manchu, or she's the docile lass whom the white man coverts but who alas will die because love between yellow and white is doomed, or he's the servile boy who faithfully serves his white master, or he's the buffoon who slurs his r's and speaks in pidgin, or the crowning example is the super detective Hawaii born Charlie Chan who speaks like a fortune cookie, but who is smarter than all whites because he finds the murder in the end, and yet he remains a stereotype and speaking sing song English is a sign that he cannot speak proper English. And still, despite living in a ghetto, the Chinese took cues from the larger US in which they lived. So, you've flappers, bootleggers, gangs, prosperous businessmen, bobby soxers, singers, actors, so and on, mirroring the broad American society.

Real political change began with Japan's war in China; geopolitical realties pushed America to support Generalissimo Chang Kai Shek as an ally. After Pearl Harbour, since America was fighting for freedom and democracy and equality for all, the houses of Congress quickly passed the Magnuson Act which lifted the restriction of the Exclusion Act of 1882, but not the quota on Chinese emigration.

From the late 1930's onwards, Hollywood film again serve as a bellwether on changing American attitudes towards China; for now you saw Chinese as doctors or respectable businessmen and educated women raising money for the Chinese fighting the common enemy Japan, along side the usual stereotypes. And of course Chinese Americans volunteered to fight in the US army, navy, and airforce.

After the end of the 'good war', things returned to business as usual but some Chinese American servicemen took advantage of the GI Bill to advance economically and socially. But on the whole, Chinatowns remained ghettos with all that meant for jobs, education, and health. The triumph of Mao Tze Tung in 1949 brought new years of threats to the Chinese in America.

A question of loyalty to Chang on Taiwan or treasonous allegiance to Mao on the mainland. The Chinese volunteer troops in the Korean War mated the US' troops to roll back Communism in Asia brought more suspicion on the growing Chinese American community. Yet, the McCarren-Walter Act of 1952 and more importantly the Immigration Act of 1965 opened wide the doors to what is called 'the second wave of Chinese immigration'. Ironically America's war in Vietnam coupled with the anti-war movement and ethnic studies exposed to public view the hidden history of Asians in America. It's not for nothing the sudden popularity of kung fu films where the hero alone with his wits and his brawn outwit opponents equipped with the latest technology, or the misguided romance with Mao's Cultural Revolution, or the reading of the I Ching or embrace of Buddhism as a panacea to a US gone off the rails.

The influx of more Chinese disrupted older patterns of leadership in the Chinatowns, made more complex class and regional distinctions, and hastened assimilation, on one hand, and the other with Nixon's trip to China in 1972, official Washington finally recognized China and not Taiwan as the spokesman for China not only normalized relations but sent a shiver of pride through this 'despised race' that the country of emigration put the land of their ancestors on an equal footing with itself. The expulsion of Chinese Vietnamese by Hanoi and the clandestine emigration of Malaysian Chinese to escape racial and economic discrimination increased the growing number of Chinese in the US.

A third wave came after Tiananmen in 1989, which began a brain drain of China's best and brightest as well as less well educated Chinese. The recent migrant held tightly on to the image of America as the 'Gold Mountain', of riches and opportunities which China would never offer them. And the American born and the immigrant Chinese became known as the 'model minority' for their embrace of the virtues America proclaimed-hard work, self reliance, the family, etc. At the same time with the influx of more immigrants the old evils of the sweat shops, prostitution, indentured servititude, gang warfare, and extortion began reappearing in expanding Chinatowns. Not so suddenly old Nativist prejudices reasserted themselves in Harvard and Berkeley for example, setting limits on Asian enrolment. Despite the protection of the law, these prejudices remain.

Today Chinese in America represent 1,17 per cent of the population and they're are a vibrant part of the US.

Article contributed by Dr. Jak Cambria

Related article:

|

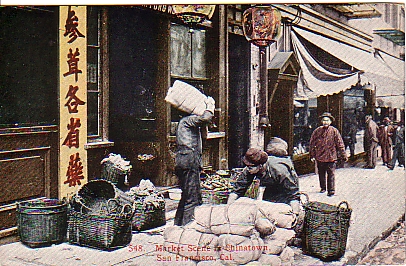

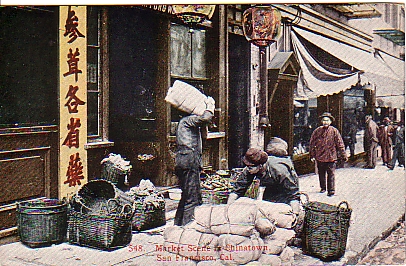

Chinese migrant in USA

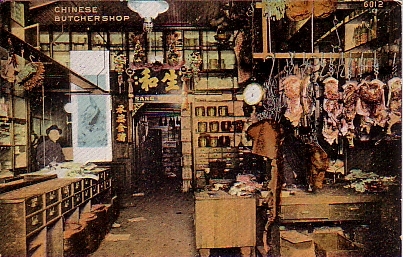

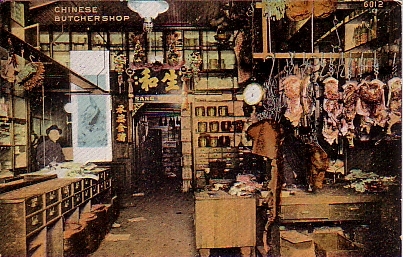

Inside a Chinese butcher shop

Chinese family in USA

Chinese delivery workers

Inside the Chinese Telephone company

Mural of Chinese railway workers

Chinese ladies on an outing

Chinese fortune teller

|

Overseas Chinese in USA

Overseas Chinese in USA Anna May Wong, Charles Wong, Hiram Fong, James Wong Howe, An Wang, David Henry Hwang, Maxine Hong Kingston, Bruce Lee, B.D. Wong, Amy Tang, Wen Ho Lee, Richard Loo, Benson Fong, Patsay Mink, Michael Chang. Chinese Americans all. It is doubtful even today that the watery eye of the average American could identity each and every name, and the mark these men and women left on America.

Anna May Wong, Charles Wong, Hiram Fong, James Wong Howe, An Wang, David Henry Hwang, Maxine Hong Kingston, Bruce Lee, B.D. Wong, Amy Tang, Wen Ho Lee, Richard Loo, Benson Fong, Patsay Mink, Michael Chang. Chinese Americans all. It is doubtful even today that the watery eye of the average American could identity each and every name, and the mark these men and women left on America.